Home » Boy Protagonist (Page 3)

Category Archives: Boy Protagonist

Antonio’s Card/ La Tarjeta de Antonio by/por Rigoberto Gonzalez

With sophisticated literary conventions, Rigoberto Gonzalez tells this bilingual story of personal growth targeted to experienced young readers. Antonio is an elementary student of Mexican heritage, born in the United States, who loves to spell and read with his mom and his mom’s partner, Leslie. These facts are all revealed slowly as the narrative unfolds. The narrative’s primary concern is establishing the relationship of a son’s love for his stepmother and the emotional quandary a son experiences when he is embarrassed by the parent he loves because of the way his peers respond to her. The fact that he has two moms is not an issue in the book. The fact that his father is absent from his daily life is revealed as a part of a scene discussing him reading with Leslie about Guadalajara, Mexico, “where Antonio’s grandparents live. His father went to live there, too, many years ago, when Antonio was just a baby.” His world is presented as normative; in fact the illustrations are of a student population at his school, that is predominantly Latino including a Latina teacher, and all except one of the children who are not Latino, are children of color.

Parents and grandparents of the children in this book represent a full range of ages, ethnicities and religious backgrounds. The sentence, “Parents of all shapes and sizes come to greet their children” cues us in to notice the differences amongst these families. We see the racial and gender differences amongst the parents and the children they are greeting easily. On a double take we notice that Leslie, Antonio’s stepmother is taller than the other adults, which seems to be the biggest difference between her and the other adults that Antonio notices, while the other children jeer about her because she “looks like a guy,” and has paint all over her from her work in the art studio, which stimulates them to belittle her as looking “like a box of crayons exploded all over her.” In response, Antonio pulls Leslie away and, despite the fact that he enjoys his time with Leslie after school every day, he asks if he can walk home by himself in the future.

This book feels sad. This is because of the tone set by the illustrations, which convey a persistent sense of yearning and longing in the eyes of almost all the characters. No one ever smiles fully, except in the family drawing Antonio makes of him and his two moms for his mother’s day card. Even when a compromised smile appears on the face of a character, their eyes overshadow any reading of complete fulfillment or happiness with a sense of worry and reflection. Although this sentimentality within the illustrations is a powerful representation of the subtext of Antonio’s worry about ending up lonely if he separates from Leslie in response to his classmates’ teasing, that feeling of a void starts on the first page, despite the fact that the narrative is well paced and complex, without being overwhelming.

While the teasing of the children seems like a mere catalyst for Antonio’s rediscovering and affirming his bond with Leslie, the imagery of the story is as weighty as the emotional milieu created by E.B. Lewis’ illustrations in Jacqueline Woodson’s Each Kindness, a book which was only about the refusal of children to befriend a new student. In Antonio’s Card/La Tarjeta de Antonio, the illustrations allude to what is unspoken in the text—a sentiment of something missing in the lives of these characters who seem to be smiling through emotional pain. Perhaps this is meant to convey the way that Antonio sees his world as one in which no one ever fully smiles and this is the way the illustrator is allowing emotions regarding the absent father who went back to Mexico to influence the text, since the author doesn’t give voice to Antonio’s feelings about his father being gone. What is clear by the end of the story is that one of the things which shames Antonio—Leslie’s splattered paint overalls— becomes evidence of Leslie’s bond with Antonio and his mother—a portrait of his mother that Leslie has painted as a Mother’s Day present. When Antonio sees the painting, his viewing of it becomes the turning point in Antonio’s journey towards family acceptance in face of the adversity of verbal teasing.

There are some who would categorize this story in the anti-bullying category of their collection and while I wouldn’t, the text and illustrations’ depthful representations of a child’s emotional vulnerability to teasing in general and especially in regards to their loved ones, makes this a story that can easily demonstrate how much words hurt in a curriculum on bullying and compassion. But, without a guide, children will easily understand Antonio’s sensitivity toward his stepmom and his peers in this story whose natural complexity and convincing narrative make it well worth its status as a Lambda Literary Finalist. (buy)

Recommendation: Highly recommended; ages 7+

Reviewer: Omilaju Miranda

Morris Micklewhite and the Tangerine Dress by Christine Baldacchino

As I finished reading this book I was saying out loud to myself: “I like it. I. Like. That.”

As I finished reading this book I was saying out loud to myself: “I like it. I. Like. That.”

This book drew me in to review it. I could not have delayed it if I wanted to. Morris Micklewhite likes his home, pancakes, and lots of things at school, including a tangerine colored dress from the dress up box. He loves the way the tangerine dress makes him think of “the sun, tigers and his mother’s hair.” He puts the tangerine dress on over his pants and black and white striped shirt, and tries different, dressy, heeled shoes from the dress up box on. Morris likes the sound the dress makes when he walks, has a favorite pair of dress shoes that make the sound “click,click, click,” enjoys his nails painted by his mom, but does not like the way boys and girls bully him at school because of the dress.

The text deals accurately with the realistic, antagonistic responses that both girls and boys have to non-conforming gender performance amongst their peers, with girls trying to pull the dress off of Morris’ body, boys excluding him from their games, and both genders verbally taunting him. Isabelle Malenfant’s pen and ink illustrations depthfully present each character’s many layered emotions and Morris’ purposeful, powerful, and vulnerable actions throughout the narrative.

Morris retreats to his home for a few days, taking refuge in his mom’s nurturing, books, puzzles, his cat and his dream. When he returns to school, he carries a painting of his dream with him, and when the boys refuse to allow him entry to their cardboard space ship, he builds one of his own. When the girls try to take the dress from him again, Morris stands up for his right to wear the tangerine dress until he is finished with it. Then, the boys who like the space ship Morris has built better than the one they built, allow Morris to lead him with his imagination and get to know him as an inventive, exploring fellow kid whose fun quotient is more important than the idea that he could change them into girls.

The winning moment of this book after we go through Morris’ journey of social challenges and self acceptance is his self-confidence, expressed in the affirmative exchange he has with a little girl in his class named Becky.

When Becky snips, “Boys don’t wear dresses.”

Morris responds, “This boy does.”

And there he goes. Morris you have the right to be you.

Whether the child you read to, or who reads this, is gender conforming or non-conforming in their play, every child will be able to understand the emotional and psycho-physio pain they have in response to being bullied and not accepted, feeling the need to step away from all peers for a little while to take a rest from bullying, and the importance of their imagination to serve as a self-soothing coping mechanism; the power of their imagination to bring them joy and instill in them a sense of pride in themselves where they may have suffered from the jabs of other children. While the standard formula often works well, one of the unique things about this book as compared to others about bullying or intolerance from children is that there are no proactive adults involved in this children’s dispute. The protagonist and his peers work out their relationships on their own– a plot choice that models independence and self-reliance for the young reader. Without Morris or the narrator saying it, the story conveys the universal message of “I can do.” to readers. (buy)

Recommendation: Highly recommended 3+

Reviewer: Omilaju Miranda

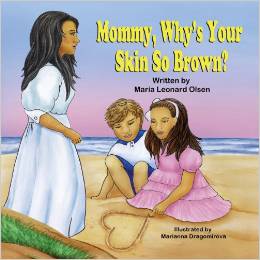

Mommy, Why’s Your Skin So Brown by Maria Leonard Olsen

The brown skinned, multiracial mixed heritage mother of two children who are lighter than her discusses with her children why she is darker than both of them and much darker than the son who has fair skin, silky blond hair, and blue eyes. The book reads as if the author simply transcribed a conversation that she had with her children. Her anger or annoyance with people who were asking the author if she was the nanny (according to interviews she has given) comes through evocatively in the tone of the narrative as well as on the book’s back cover blurb, which both address the necessity to admonish people to not allow their “curiosity to overwhelm their manners”.

The brown skinned, multiracial mixed heritage mother of two children who are lighter than her discusses with her children why she is darker than both of them and much darker than the son who has fair skin, silky blond hair, and blue eyes. The book reads as if the author simply transcribed a conversation that she had with her children. Her anger or annoyance with people who were asking the author if she was the nanny (according to interviews she has given) comes through evocatively in the tone of the narrative as well as on the book’s back cover blurb, which both address the necessity to admonish people to not allow their “curiosity to overwhelm their manners”.

That is a salient point that many parents of interracial families would like to communicate to those who rudely ask questions like “Are you the nanny?” “Is she adopted?” “Is that child yours?”, which confuse and sometimes sadden our children. However, in a children’s book, the tone of the mother’s frustration doesn’t communicate as a part of the children’s characterization and reads as the words of an angry author. It just doesn’t feel like it is from the children, and there’s nothing in the narrative to balance it off.

Points of the narrative that could have been the basis for beautiful illustrations of the entire family are missed. This conversation between the mother and her children is boring as a book read to a child and there are points that actually get confusing where the mother narrator is discussing where everybody got their different features (i.e. the mother speaks of getting her own dark skin from her grandmother, herself being a color in between both her parents, and her son getting blue eyes from his father and the mother’s grandfather) yet there are no images of the relatives to accompany this monologue.

This lack of illustration accompanied by no mention of the mother’s actual ethnicity (research into the author reveals she is biracial Filipina and this story is from her personal life) seems like a strong commitment to being vague. I’m sure the author doesn’t mention the ethnic heritages of her family so that the book could be used universally by the many parents of color of all ethnicities and races who face this scenario but because this book’s only story line is this family, the absence of a discussion of the family’s ethnicity and actual heritage leaves a palpable void. With no characterization for any of the characters in the book and a narration primarily from the mother’s perspective, sadly there is no story here. This is such a loss in part because this is the only picture book I’ve read that focuses primarily on the biracial child with almost exclusively Caucasian features. The other books which even present these children, present them as part of a duo led by brown biracial children or as part of an ensemble cast.

While I do not see this as an enjoyable read for children of any age as a standalone book, this book could easily serve as an interesting guide for adults on how to discuss this matter with their children and the points that can be covered regarding family features. If used in that matter, I would definitely suggest incorporating photos of the referenced family members into the conversation. (buy)

Recommendation: If your family is similar to the one in this book then, couple this book with your own family photos and exploration of your family tree or, for people with all types of family constructs and teachers, couple this book with either That’s My Mum by Henriette Barkow or My Mom is a Foreigner but Not to Me by Julianne Moore and this book can lead off the discussion of the serious aspects of a family dealing with people’s reactions to a mother (or father) looking racially different from her children.

Recommendations: For Adults to lead discussions on interracial families and phenotype differences.

Reviewer: Omilaju Miranda

Every Little Thing by Cedella and Bob Marley with by Vanessa Brantley-Newton

Every Little Thing, Cedella Marley’s adaptation of Bob Marley’s song Every Little Thing could be called the companion book to Marley’s adaptation of her father’s One Love song. This time, the protagonist is a little boy from a loving family who spreads the joy and comfort that his parents give him through their affection and forgiveness, with other kids. Once again, Brantley-Newton’s illustrations powerfully tell a story with Marley’s words serving as the lyrical underscore for what is happening. I couldn’t help singing this book to my daughter and she easily and happily sang along in between asking questions about what was going on in the story. The narrative starts when the protagonist wakes up in the morning, follows him through a day of playing in the rain, and sun, enjoying time with his pets and three little birds, as well as his friends. He befriends a shy and isolated friend, makes a mess of his kitchen trying to bake a cake, is forgiven by his parents, sulks about bedtime, before his parents hug him and tuck him in, then he awakens in the next morning happy again. While the cast of characters is much smaller than that in One Love, a fair representation of black and white characters with different phenotypes is present. I was particularly happy to see an Asian child included as the subject of the protagonist’s friendship in the illustrations of this book as Asians were absent from the book One Love. Without question, this book is a joy to read, and once again the illustrations are perfect for the pre-literate child to practice “reading” comprehension skills in decoding the story told by the illustrations.

Every Little Thing, Cedella Marley’s adaptation of Bob Marley’s song Every Little Thing could be called the companion book to Marley’s adaptation of her father’s One Love song. This time, the protagonist is a little boy from a loving family who spreads the joy and comfort that his parents give him through their affection and forgiveness, with other kids. Once again, Brantley-Newton’s illustrations powerfully tell a story with Marley’s words serving as the lyrical underscore for what is happening. I couldn’t help singing this book to my daughter and she easily and happily sang along in between asking questions about what was going on in the story. The narrative starts when the protagonist wakes up in the morning, follows him through a day of playing in the rain, and sun, enjoying time with his pets and three little birds, as well as his friends. He befriends a shy and isolated friend, makes a mess of his kitchen trying to bake a cake, is forgiven by his parents, sulks about bedtime, before his parents hug him and tuck him in, then he awakens in the next morning happy again. While the cast of characters is much smaller than that in One Love, a fair representation of black and white characters with different phenotypes is present. I was particularly happy to see an Asian child included as the subject of the protagonist’s friendship in the illustrations of this book as Asians were absent from the book One Love. Without question, this book is a joy to read, and once again the illustrations are perfect for the pre-literate child to practice “reading” comprehension skills in decoding the story told by the illustrations.

Recommendation: Highly Recommended ages 0+

Reviewer: Omilaju Miranda

Dear Primo: a Letter to my Cousin by Duncan Tonatiuh

Comparing Cultures, A Review of Duncan Tonatiuh’s “Dear Primo: a Letter to my Cousin”

Comparing Cultures, A Review of Duncan Tonatiuh’s “Dear Primo: a Letter to my Cousin”

This epistolary children’s book not only fills a much needed niche in the narrative for children living in America, it gives us a glimpse into a different kind of family structure, a family structure whose existence is an arbitrary border away.

Charlie, the Mexican-American boy living in New York, experiences life as an assimilated child: basketball, pizza, and video games; while his cousin, Carlitos, a village dweller in Mexico, experiences a similar but different experience: his sport is soccer, his cheese is found in a quesadilla and his games are found in the beauty of his natural environment. The two kids’ lives mimic one another; one is associated with the other in a way that would be interesting to a child, if cliche for adults.

Children like familiarity which is provided through Charlie’s perspective, but children also respond to new sounds, so the sprinkling of Spanish is welcomed. Familiar Spanish nouns like perros (dogs) and gallo (rooster) are introduced as captions or interjections which provide intertextual experience; you and your child could spend extra time on the page isolating those words and building a small vocabulary.

But the most amazing part of this book is beyond the words: the illustrations! These full-page, hand-drawn, hand-colored images are warm with the color of earth when we experience Carlitos’ narrative and steely cool when Charlie’s sterile city scene is set. The boys are boxy and asymmetrical with profile-facing, round heads in a style reminiscent of Mayan art. The boys are modern versions of their ancestors: a mixture of animal and human, earth and man; even their spirally fists are imaginative.

This book presents two cultures which overlap and exist on the same continent. Two cultures positioned in contrasting contexts: different settings in the same family.

Recommendation: Highly recommended, ages 4 – 8

Book Review by: Rachelle Escamilla

Maxwell’s Mountain by Shari Becker

Maxwell’s Mountain features a little boy with an Asian-featured father and Caucasian-looking, redheaded mother. Maxwell sees a mountain near a new park, and goes on a mountain-climbing adventure. The illustrations are beautiful watercolor-and-ink, though the story, while it teaches some good lessons, could have been so much more.

Maxwell’s Mountain features a little boy with an Asian-featured father and Caucasian-looking, redheaded mother. Maxwell sees a mountain near a new park, and goes on a mountain-climbing adventure. The illustrations are beautiful watercolor-and-ink, though the story, while it teaches some good lessons, could have been so much more.

The story could have addressed the diversity so lovingly depicted by the illustrations. If you have a mixed family, you and your child might enjoy seeing the representation of diversity here. It’s interesting that the author says nothing about Maxwell’s family and background, however—not only is this a missed opportunity, it feels like a multi-racial elephant in the room.

The actual morals tackled here also seem ambiguous. One lesson a child might learn from this story is to be prepared before undertaking a large task. Maxwell is determined to the point of obsession (“At dinner Maxwell saw mountains everywhere”) and does his research by (unrealistically) checking out all the books on mountain-climbing from the library and looking through them all in one night. He trains for his hike by repeatedly climbing up and down the stairs at home (depending on the age of your child, maybe not the safest activity to encourage). And the overt moral of the book is, “When he’s in trouble, a true outdoorsman uses his head.” The gendered “outdoorsman” and “he/his” throughout the book can be limiting gender-wise, and in the end, Maxwell doesn’t really use his head that much besides backtracking a little when he gets lost.

In conclusion, Maxwell’s Mountain features lovely and intriguing illustrations, though the story does not live up to its full potential. We might wish the world were post-racial and post-feminist, that race and gender are no longer issues we should give voice to for children when an obvious opportunity presents itself, but we’re not quite there yet.

Recommendation: 4-8 years. (buy)

Review by Yu-Han (Eugenia) Chao