Home » Girl Protagonist (Page 4)

Category Archives: Girl Protagonist

When the Black Girl Sings by Bil Wright

If When the Black Girl Sings by Bil Wright was a dish served at a fancy restaurant it would be described as “adoption woes over a bed of teenage angst served with a side of parental problems and an empty glass of communication.” Doesn’t sound like a favorite dish you would order time after time, but it does fill a definite need on the menu.

If When the Black Girl Sings by Bil Wright was a dish served at a fancy restaurant it would be described as “adoption woes over a bed of teenage angst served with a side of parental problems and an empty glass of communication.” Doesn’t sound like a favorite dish you would order time after time, but it does fill a definite need on the menu.

The main character, Lahni, is a 13 year old black girl who was adopted by white, heterosexual parents when she was a baby. Living with white parents in Connecticut, Lahni attends a private school, with only a handful of non-white students. She feels completely out of place, alone and unable to connect with friends. Adding to her troubles, her parents are getting a divorce and her father has a new “friend”. Then her mother suggests they try going to church, where Lahni meets and befriends the choir director and the church’s soloist who are both black. She is coerced by her music teacher, who sees promise in her, into joining a singing competition at her school. Lahni joins her church choir to help her prepare for the competition and in the end finds her voice.

I found at many times in this book I was frustrated with Lahni and her parents mainly because they seemed to be hopeless at communicating honestly with one another and others around them. After a particularly upsetting incident at school where a classmate calls Lahni an “African baby on a television special” her mom says, “Maybe she meant it as a compliment.” Or when Lahni’s dad finds her waiting outside the door listening to her parents scream at one another, he simply takes his suitcase and gets into the taxi. Lahni, following the role models set out for her, never talks with her parents (or anyone) about how it feels to be a black child adopted by a white family or about the troubles she has as the only black girl in her grade. Lahni keeps her best friend at bay, only telling her about her parents impending divorce at the very end and then again shuts her friend down when she asks questions. Lahni’s struggle with communication does not end with her inability to share her thoughts, but it seems she is not able to garner messages others are telling her as well. Her music teacher and choir director clearly express on multiple occasions their admiration for her singing, yet even to the end Lahni refuses to have confidence in her ability. That said, the teenage years are not perfect. Transracial adoption is not always heart-to-heart chats and a warm cup of cocoa. And I am NOT a black, teenage girl being raised by struggling white parents, so perhaps I just don’t get it. And perhaps there is some reader in Lahni’s exact situation who will want to take Lahni into her heart because she is singing the reader’s song.

At one point in the story, Lahni is being stalked by a white boy in school who calls himself Onyx 1. This boy focuses his affection on Lahni purely based on his desire to date a black girl. Later he gets in a knife fight with two black boys and he calls them “two black apes”. When Lahni hears this, she is so confused about how a person can want to date someone who is black, nickname themselves “black” and then use racial slurs. In typical teenage style, although scared of Onyx 1, she chooses to handle it on her own. Lahni never mentions it to her parents or to another adult until the end of the book after she is forced in a deserted parking lot to confront him. I dislike the fact that the author had Lahni deal with this issue on her own. Obviously, in fiction the author managed the confrontation to work out in Lahni’s favor but in real life confronting a stalker is truly dangerous. I want the message to young adult readers to clearly state, “ask for help from an adult if this happens to you.” I did however like that the author kept Onyx 1’s character as undesirable and Lahni told him to get lost. Too many times, plots include the “good girl” falling for a “bad boy” when she discovers his soft side.

This book has a light Christian theme to it, but it is not overwhelming. In the beginning Lahni attends church for the first time and by the end she performs “His Eye is on the Sparrow” and realizes she is not singing but she is in fact praying.

Recommendation: This book is suitable for readers age 13+.

Reviewer: Amanda Setty

The Favorite Daughter by Allen Say

Many of us with foreign or (to Americans) impossible-to-pronounce names will relate to Yuriko’s conflicts in The Favorite Daughter—people make fun of and butcher her name so she wants an Americanized one without cultural or linguistic baggage. There’s also an additional layer of complexity to Yuriko’s identity—she’s mixed (there are two photographs of the real Yuriko in the book: she has blonde hair and Asian facial features). In addition, since the book begins with “Yuriko came to stay with her father on Thursday that week,” this may be a divorced family as well. Allen Say navigates all of these complexities with grace, subtlety, humor, and most of all, love.

Many of us with foreign or (to Americans) impossible-to-pronounce names will relate to Yuriko’s conflicts in The Favorite Daughter—people make fun of and butcher her name so she wants an Americanized one without cultural or linguistic baggage. There’s also an additional layer of complexity to Yuriko’s identity—she’s mixed (there are two photographs of the real Yuriko in the book: she has blonde hair and Asian facial features). In addition, since the book begins with “Yuriko came to stay with her father on Thursday that week,” this may be a divorced family as well. Allen Say navigates all of these complexities with grace, subtlety, humor, and most of all, love.

Yuriko is upset that her classmates tease her after she shares a baby picture at school, and the new art teacher mispronounces her name. At home, she tells her Japanese father she wants an American name, “Michelle”. He goes along with it, saying “Michelle” is his new daughter, even introducing her as such to the owner of a Japanese restaurant. When she acquiesces to letting the owner call her Yuriko, he gives her a bundle of disposable chopsticks as a gift.

That weekend Yuriko and her father go to San Francisco because she has to draw the Golden Gate Bridge for the new art teacher. But first, her father takes her on a “real quick trip” to “Japan.” They visit a Japanese garden and a Japanese ink painting master gifts her with a painting of a lily, as Yuriko means “child of the lily” (a nod to a Caucasian mother?). He writes her name in Japanese, and Yuriko says, “I’m going to learn to write it.” Unfortunately, by the time Yuriko sees the Golden Gate Bridge, it’s covered with thick fog. She sulks, thinking her art project is doomed.

But things work out: Monday morning Yuriko returns to school owning her name/identity as well as a creative piece called “the Golden Gate in the fog” (disposable chopsticks and cotton). She signs the project Yuriko, not Michelle, to which her father responds, “That’s my favorite daughter!”

Recommendation: Highly Recommended. 4-8 years.

Reviewer: Yu-Han Chao.

Always an Olivia: A Remarkable Family History by Caroliva Herron

Heartbreaking, historically informative, and beautifully illustrated, Always An Olivia:A Remarkable Family History is the true family history of scholar and author, Olivia Herron (Nappy Hair) whose family has preserved their Jewish traditions even seven generations removed from the family’s Jewish matriarch. While the story is being told to a granddaughter in 2007 by her great-grandmother, the narrative actually tells the story of their ancestor Sarah who, hundreds of years ago, was the Italian Jewish granddaughter of victims of Jewish pogroms in Spain and Portugal. She is captured by pirates to be ransomed off but saved by another captive with whom she falls in love and sails to the USA to avoid recapture, death or the burning of the homes and businesses of the Jews to whom she was supposed to be ransomed. Still afraid of anti-Jewish violence, Sarah adopts the middle name Olivia instead of using her given middle name, Shulamit.

In the U.S., customs settles Sarah and her husband on the Georgia Islands in the free, black African Geechee community. Sarah and her husband have children and their children marry Geechees. Their descendants continue to practice the Jewish rituals that Sarah remembered (because, the text lets us know, she forgot many) including lighting the Shabbat candles on Friday nights. The women are the keepers of the tradition from being in charge of lighting the Shabbat candles to the legacy of naming a daughter of each generation Olivia or, as Sarah requested, a name that means “peace”. They choose to preserve the original name by naming a girl in each generation “Olivia” after Sarah.

From the opening line in which the girl child Carol Olivia asks her great-grandmother about black U.S.American slavery and is told that her family experienced enslavement in Egypt, witnessed U.S.American chattel slavery, but was not descended from enslaved black U.S.Americans, this biography is an eye opening account of the different histories of blacks and mixed racial heritage people in the U.S. since the 16th century.

Despite the book’s engagement of the heavy subject matter of slavery, racial and religious persecution, kidnapping, family separation, and near identity loss, there is a hopeful tone in the reading, achieved through James Tugeau’s use of light in his dramatic pastel illustrations, the tone of the narrative, and narrative breaks in the relaying of violence to fully describe life in peaceful times. Thus, this story of a resilient family communicates the necessity of remembering family history. Always an Olivia makes it clear that despite their family history of terror, renewal, survival and reinvention, the family of Olivias is proud of, and takes comfort in, their family traditions and heritage.

Recommendation: Highly Recommended; Ages 8-Adult (buy)

Reviewer: Omilaju Miranda

I Am a Ballerina by Valerie Coulman

The pastel drawings of I Am a Ballerina are soft and subtle, and the story straightforward and sweet. Not overly pink and frilly, and not going too deep below the surface of a little girl exploring a new passion, this book would be a great read for children considering a new sport or interest.

The pastel drawings of I Am a Ballerina are soft and subtle, and the story straightforward and sweet. Not overly pink and frilly, and not going too deep below the surface of a little girl exploring a new passion, this book would be a great read for children considering a new sport or interest.

After watching a ballet performance on her birthday, little Molly decides that she is a ballerina. At first her parents’ response to her leaping around the house in imitation of the gazelle-like picture of a ballerina on her wall is, “Jump down, dear.” When she smears her face with baby-blue eyeshadow and rouge, announcing herself as beautiful as a ballerina, her mother tells her to, “Go wash your face, dear.” Finally, after she nearly knocks some things over, her father concedes: “If you’re going to be a ballerina, maybe you should take some lessons.”

At Madame Cherie’s ballet school, Molly falls and trips, but it’s all part of learning. She practices and practices, and finally dons a merry-go-round horse costume for the ballet performance. The moment at the end of the book that Molly truly feels like she is a ballerina, however, is when her father lifts airplane-style: “It felt like flying. And then I knew…I am a ballerina.”

As seen in some “diverse” children’s books, the author plays it safe, saying nothing about ethnicity or appearance, even though the illustrator makes a point of creating a distinctly mixed family. Molly’s father is Caucasian or mixed, with curly brown hair and a bushy moustache, whereas her mother is Asian-featured. In this case, however, since it’s a nice ballet story that’s realistic and not overly pink and filled with tutus, I don’t mind that Asian-looking Molly isn’t identified ethnically or culturally (for all we know, her father is her stepfather, or she’s adopted).

Recommendation: Recommended: 4-6 years

Reviewer: Yu-Han Chao

Visiting my Father’s Homeland: Book Review for I Lost My Tooth in Africa by Penda Diakité

Losing teeth is a rite of passage for every child and, based on twelve-year-old Penda Diakité’s I Lost My Tooth in Africa, a visit from the elusive tooth-fairy is a welcome surprise for children all over the world as well—even in Mali, West Africa!

In the story, Amina, a girl born and raised in the U.S., and her family travel from Portland, Oregon to Bamako, Mali, her father’s birthplace and childhood home. Amina’s loose tooth—which she discovers while en route to Mali— tags along. After her father shares with her that the African tooth fairy trades a chicken in exchange for a little boy or girl’s tooth, Amina is determined to lose her wiggly tooth before this family trip to Africa is over.

Infused with a strong representation of words from Bamabara (a glossary is in the back of the book), the most widely used indigenous language of Mali, and Malian cultural traditions, I Lost My Tooth in Africa is a mildly suspenseful narrative that children between the ages of 5 and 8 who are also going through the “snaggle-tooth” phase could especially appreciate while learning informative tidbits about a new culture and geographical location. The children in your life will be further inspired by the fact that this book, published by one of the five major publisher’s of children’s books, is the creation of a pre-teen author and her illustrator father.

Recommendation: Highly Recommended ages 5-8

Reviewer: LaTonya Jackson

I am Me by Karla Kushkin

Concisely written, Karla Kushkin’s I Am Me is a biracial little girl’s declaration of pride in both the physical characteristics that connect her to the people in her family as well as her self-pride in her individuality. She is a mixture of various characteristics of her father, her mother, and their respective families. Although the race or ethnicity of her father is not clear, he is a man of color, while her mother is Caucasian. With tawny skin and dark hair like her father and light green eyes like her mother, she is an apparent blend of two distinctly different ethnicities. Dyanna Wolcott’s illustrations emphasize the physical contrast between the two families (and the differences between the little girl and her parents) as they mingle together on an outing at the park filled with swimming, bike-riding, and a picnic. The text and illustrations are rendered in a manner that mimics a child’s innocent observations and the playfulness of the narrative and images makes this book visually and audibly attractive and relatable to a younger audience.

Recommendation: recommended ages 3+

Reviewer: LaTonya Jackson

Marisol McDonald and the Clash Bash/ Marisol McDonald y la fiesta sin igual by/por Monica Brown

Monica Brown once again delivers a captivating protagonist in the character of Marisol McDonald whose bilinguality, red-headed, brown-skinned physical traits, and mixed Peruvian-Scottish-U.S.American ethnic heritage are significant influences on her daily life. Marisol McDonald became one of my favorite children’s literature characters in the first book in this series, Marisol McDonald Doesn’t Match. This time around, Marisol is days away from her eighth birthday. While she doesn’t want to choose clothes or a party theme that match, she does want to see her abuelita (grandmother) for her birthday. However, Marisol must deal with the disappointing reality that, despite the fact that she has been doing chores and saving money for two years to pay for her abuelita to visit, a visa for her grandmother to visit the U.S. takes too much time for abuelita to arrive before Marisol’s birthday. With the strategic use of hand made, individualized party invitations to her diverse, multicultural group of friends, Marisol is able to get her mismatched costume birthday party and her abuelita finds a special, and realistic way to make an appearance. The story is told in a rich, first person point of view, which includes a sprinkling of Spanish in the English version and a sprinkling of English in the Spanish version so the reader always feels as if they are living in Marisol’s authentic bilingual world. Palacios’ painted illustrations add to the overall cheer of enjoying this book. And the dual language, English/Spanish telling of the story allow the reader to read the story in both languages in one sitting or read it in English one day and Spanish the next day.

Monica Brown once again delivers a captivating protagonist in the character of Marisol McDonald whose bilinguality, red-headed, brown-skinned physical traits, and mixed Peruvian-Scottish-U.S.American ethnic heritage are significant influences on her daily life. Marisol McDonald became one of my favorite children’s literature characters in the first book in this series, Marisol McDonald Doesn’t Match. This time around, Marisol is days away from her eighth birthday. While she doesn’t want to choose clothes or a party theme that match, she does want to see her abuelita (grandmother) for her birthday. However, Marisol must deal with the disappointing reality that, despite the fact that she has been doing chores and saving money for two years to pay for her abuelita to visit, a visa for her grandmother to visit the U.S. takes too much time for abuelita to arrive before Marisol’s birthday. With the strategic use of hand made, individualized party invitations to her diverse, multicultural group of friends, Marisol is able to get her mismatched costume birthday party and her abuelita finds a special, and realistic way to make an appearance. The story is told in a rich, first person point of view, which includes a sprinkling of Spanish in the English version and a sprinkling of English in the Spanish version so the reader always feels as if they are living in Marisol’s authentic bilingual world. Palacios’ painted illustrations add to the overall cheer of enjoying this book. And the dual language, English/Spanish telling of the story allow the reader to read the story in both languages in one sitting or read it in English one day and Spanish the next day.

My four-year-old who is rather good at decoding and following a good story didn’t follow all the detailed nuances that go along with Marisol choosing not to match and wasn’t as excited about this story as I was so I put target audience at just slightly older and a better fit for the child who can already read. The quality of the story should make it a favorite for children beyond the age of ten even though they will have already moved on to higher reading levels. For the 5-8 year old reader, new vocabulary is emphasized that will make them excitedly run to the dictionary so they can understand every single word and emotion of this spunky, energetic protagonist. I want to see so much more of Marisol McDonald. Once again, think Madeleine, think Eloise, think Olivia the Pig, think Orphan Annie all updated and in a Peruvian-Scottish U.S.American girl. l I love this character; you and your kids will as well. (buy

Recommendations: Highly Recommended Ages 5-8+

Reviewer: Omilaju Miranda

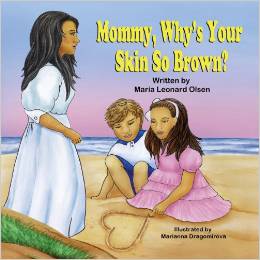

Mommy, Why’s Your Skin So Brown by Maria Leonard Olsen

The brown skinned, multiracial mixed heritage mother of two children who are lighter than her discusses with her children why she is darker than both of them and much darker than the son who has fair skin, silky blond hair, and blue eyes. The book reads as if the author simply transcribed a conversation that she had with her children. Her anger or annoyance with people who were asking the author if she was the nanny (according to interviews she has given) comes through evocatively in the tone of the narrative as well as on the book’s back cover blurb, which both address the necessity to admonish people to not allow their “curiosity to overwhelm their manners”.

The brown skinned, multiracial mixed heritage mother of two children who are lighter than her discusses with her children why she is darker than both of them and much darker than the son who has fair skin, silky blond hair, and blue eyes. The book reads as if the author simply transcribed a conversation that she had with her children. Her anger or annoyance with people who were asking the author if she was the nanny (according to interviews she has given) comes through evocatively in the tone of the narrative as well as on the book’s back cover blurb, which both address the necessity to admonish people to not allow their “curiosity to overwhelm their manners”.

That is a salient point that many parents of interracial families would like to communicate to those who rudely ask questions like “Are you the nanny?” “Is she adopted?” “Is that child yours?”, which confuse and sometimes sadden our children. However, in a children’s book, the tone of the mother’s frustration doesn’t communicate as a part of the children’s characterization and reads as the words of an angry author. It just doesn’t feel like it is from the children, and there’s nothing in the narrative to balance it off.

Points of the narrative that could have been the basis for beautiful illustrations of the entire family are missed. This conversation between the mother and her children is boring as a book read to a child and there are points that actually get confusing where the mother narrator is discussing where everybody got their different features (i.e. the mother speaks of getting her own dark skin from her grandmother, herself being a color in between both her parents, and her son getting blue eyes from his father and the mother’s grandfather) yet there are no images of the relatives to accompany this monologue.

This lack of illustration accompanied by no mention of the mother’s actual ethnicity (research into the author reveals she is biracial Filipina and this story is from her personal life) seems like a strong commitment to being vague. I’m sure the author doesn’t mention the ethnic heritages of her family so that the book could be used universally by the many parents of color of all ethnicities and races who face this scenario but because this book’s only story line is this family, the absence of a discussion of the family’s ethnicity and actual heritage leaves a palpable void. With no characterization for any of the characters in the book and a narration primarily from the mother’s perspective, sadly there is no story here. This is such a loss in part because this is the only picture book I’ve read that focuses primarily on the biracial child with almost exclusively Caucasian features. The other books which even present these children, present them as part of a duo led by brown biracial children or as part of an ensemble cast.

While I do not see this as an enjoyable read for children of any age as a standalone book, this book could easily serve as an interesting guide for adults on how to discuss this matter with their children and the points that can be covered regarding family features. If used in that matter, I would definitely suggest incorporating photos of the referenced family members into the conversation. (buy)

Recommendation: If your family is similar to the one in this book then, couple this book with your own family photos and exploration of your family tree or, for people with all types of family constructs and teachers, couple this book with either That’s My Mum by Henriette Barkow or My Mom is a Foreigner but Not to Me by Julianne Moore and this book can lead off the discussion of the serious aspects of a family dealing with people’s reactions to a mother (or father) looking racially different from her children.

Recommendations: For Adults to lead discussions on interracial families and phenotype differences.

Reviewer: Omilaju Miranda

Lulu’s Busy Day

Lulu’s Busy Day is the sequel to Hello, Lulu and this time around we learn about the daily activities of our main character (while her heritage is again sidestepped). Drawing, visiting the park with a friend, and building castles is all in a day’s work for Lulu. While the first Lulu book visually suggests that she’s biracial by introducing us to her parents, this book also prefers to visually cue us in on her differences: her brown, puffy hair, dark eyes, and tan complexion. So while she looks a little different compared to many popular storybook characters, she still does all the same things as everyone else. Thus, this would be a good book to share with your child to introduce them to a diverse character—just make sure you point it out to your young reader.

Lulu’s Busy Day is the sequel to Hello, Lulu and this time around we learn about the daily activities of our main character (while her heritage is again sidestepped). Drawing, visiting the park with a friend, and building castles is all in a day’s work for Lulu. While the first Lulu book visually suggests that she’s biracial by introducing us to her parents, this book also prefers to visually cue us in on her differences: her brown, puffy hair, dark eyes, and tan complexion. So while she looks a little different compared to many popular storybook characters, she still does all the same things as everyone else. Thus, this would be a good book to share with your child to introduce them to a diverse character—just make sure you point it out to your young reader.

Recommendation: Recommended to introduce young readers to diverse-looking characters; Ages 2-5

Reviewer: Kaitlyn Wells

Hello, Lulu by Caroline Uff

Hello, Lulu is a great book for beginner readers, but not necessarily the ideal book if you’re teaching your little one about diversity. The book introduces the reader to a little girl named Lulu and the important people and things in her life. The reader learns about Lulu and all of the members of her family. The board book itself features brightly colored backgrounds to help Lulu’s family members stand out. So while the illustrations visually cue us in on the family’s interracial composition, it’s never verbally explained. Thus, to bypass this subliminal message, you may want to point out the fact that Lulu’s parents are different races from the beginning. One other note: From learning about what Lulu’s favorite snacks are to how many pets Lulu has, your child is sure to notice a correlation or two in their own life (racial composition aside).

Hello, Lulu is a great book for beginner readers, but not necessarily the ideal book if you’re teaching your little one about diversity. The book introduces the reader to a little girl named Lulu and the important people and things in her life. The reader learns about Lulu and all of the members of her family. The board book itself features brightly colored backgrounds to help Lulu’s family members stand out. So while the illustrations visually cue us in on the family’s interracial composition, it’s never verbally explained. Thus, to bypass this subliminal message, you may want to point out the fact that Lulu’s parents are different races from the beginning. One other note: From learning about what Lulu’s favorite snacks are to how many pets Lulu has, your child is sure to notice a correlation or two in their own life (racial composition aside).

Recommendation: Recommended to introduce young readers to diverse-looking characters; Ages 2-5 (buy)

Book Reviewers: Kaitlyn Wells