Home » Posts tagged 'bilingual' (Page 3)

Tag Archives: bilingual

The Favorite Daughter by Allen Say

Many of us with foreign or (to Americans) impossible-to-pronounce names will relate to Yuriko’s conflicts in The Favorite Daughter—people make fun of and butcher her name so she wants an Americanized one without cultural or linguistic baggage. There’s also an additional layer of complexity to Yuriko’s identity—she’s mixed (there are two photographs of the real Yuriko in the book: she has blonde hair and Asian facial features). In addition, since the book begins with “Yuriko came to stay with her father on Thursday that week,” this may be a divorced family as well. Allen Say navigates all of these complexities with grace, subtlety, humor, and most of all, love.

Many of us with foreign or (to Americans) impossible-to-pronounce names will relate to Yuriko’s conflicts in The Favorite Daughter—people make fun of and butcher her name so she wants an Americanized one without cultural or linguistic baggage. There’s also an additional layer of complexity to Yuriko’s identity—she’s mixed (there are two photographs of the real Yuriko in the book: she has blonde hair and Asian facial features). In addition, since the book begins with “Yuriko came to stay with her father on Thursday that week,” this may be a divorced family as well. Allen Say navigates all of these complexities with grace, subtlety, humor, and most of all, love.

Yuriko is upset that her classmates tease her after she shares a baby picture at school, and the new art teacher mispronounces her name. At home, she tells her Japanese father she wants an American name, “Michelle”. He goes along with it, saying “Michelle” is his new daughter, even introducing her as such to the owner of a Japanese restaurant. When she acquiesces to letting the owner call her Yuriko, he gives her a bundle of disposable chopsticks as a gift.

That weekend Yuriko and her father go to San Francisco because she has to draw the Golden Gate Bridge for the new art teacher. But first, her father takes her on a “real quick trip” to “Japan.” They visit a Japanese garden and a Japanese ink painting master gifts her with a painting of a lily, as Yuriko means “child of the lily” (a nod to a Caucasian mother?). He writes her name in Japanese, and Yuriko says, “I’m going to learn to write it.” Unfortunately, by the time Yuriko sees the Golden Gate Bridge, it’s covered with thick fog. She sulks, thinking her art project is doomed.

But things work out: Monday morning Yuriko returns to school owning her name/identity as well as a creative piece called “the Golden Gate in the fog” (disposable chopsticks and cotton). She signs the project Yuriko, not Michelle, to which her father responds, “That’s my favorite daughter!”

Recommendation: Highly Recommended. 4-8 years.

Reviewer: Yu-Han Chao.

Yoko Writes Her Name by Rosemary Wells

Rosemary Wells’s Yoko Writes Her Name, a contemporary fable about linguistic difference, shows what kindergarten might be like for an ELL (English Language Learner) kitten or child. Through this book a child might learn some good lessons about diversity, forgiveness, and acceptance. Little gray tabby Yoko speaks and reads out loud in English, but writes in Japanese, and that is how the whole story and conflict begins.

The first time the teacher asks everyone to write their names, Yoko writes hers in Japanese, and the teacher acknowledges “How beautifully Yoko writes in Japanese,” but two other kittens in kindergarten whisper, “Yoko can’t write. She is only scribbling!” “She won’t graduate from kindergarten!” Things get worse when the teacher invites Yoko to bring a book from home to read to the class and she reads it from right to left, not left to right. “Yoko is only pretending to read!” “She’ll never make it to first grade!” the mean kittens say.

Yoko feels forlorn and dejected until a gray mouse seeks her out and admires her “secret language.” She teaches him how to write out numbers in Japanese, and soon all the little animals want to write their names in Japanese. On parent’s night, Yoko’s mother brings in a big Japanese alphabet and the teacher declares that Japanese will be the class’s second language.

Soon Japanese is everywhere in the classroom, and all the little animals, with the exception of the two mean kittens, learn to write their names in Japanese. On graduation day, the class writes their names in two languages on their diploma, but the two mean kittens hide in the closet, worried they won’t graduate. Yoko finds them and teaches them to write their names in Japanese—just in time to join the graduation march.

While this book makes Japanese seem easier to learn than it might be for a kindergarten teacher and her class, it’s a nice ideal of how such a conflict would be resolved in a fantasy world. The illustrations are adorable, and in the top corners of facing pages the author/illustrator provides a small picture of things like a cup or a dog, and its corresponding page is the Japanese translation. You or your child probably won’t pick up Japanese from this book if you don’t already read and speak it a little, but this is the kind of multicultural text schools and libraries should have to celebrate diversity and inclusion.

Recommendation: Recommended: 3-6 years

Reviewer: Yu-Han Chao

Visiting my Father’s Homeland: Book Review for I Lost My Tooth in Africa by Penda Diakité

Losing teeth is a rite of passage for every child and, based on twelve-year-old Penda Diakité’s I Lost My Tooth in Africa, a visit from the elusive tooth-fairy is a welcome surprise for children all over the world as well—even in Mali, West Africa!

In the story, Amina, a girl born and raised in the U.S., and her family travel from Portland, Oregon to Bamako, Mali, her father’s birthplace and childhood home. Amina’s loose tooth—which she discovers while en route to Mali— tags along. After her father shares with her that the African tooth fairy trades a chicken in exchange for a little boy or girl’s tooth, Amina is determined to lose her wiggly tooth before this family trip to Africa is over.

Infused with a strong representation of words from Bamabara (a glossary is in the back of the book), the most widely used indigenous language of Mali, and Malian cultural traditions, I Lost My Tooth in Africa is a mildly suspenseful narrative that children between the ages of 5 and 8 who are also going through the “snaggle-tooth” phase could especially appreciate while learning informative tidbits about a new culture and geographical location. The children in your life will be further inspired by the fact that this book, published by one of the five major publisher’s of children’s books, is the creation of a pre-teen author and her illustrator father.

Recommendation: Highly Recommended ages 5-8

Reviewer: LaTonya Jackson

Antonio’s Card/ La Tarjeta de Antonio by/por Rigoberto Gonzalez

With sophisticated literary conventions, Rigoberto Gonzalez tells this bilingual story of personal growth targeted to experienced young readers. Antonio is an elementary student of Mexican heritage, born in the United States, who loves to spell and read with his mom and his mom’s partner, Leslie. These facts are all revealed slowly as the narrative unfolds. The narrative’s primary concern is establishing the relationship of a son’s love for his stepmother and the emotional quandary a son experiences when he is embarrassed by the parent he loves because of the way his peers respond to her. The fact that he has two moms is not an issue in the book. The fact that his father is absent from his daily life is revealed as a part of a scene discussing him reading with Leslie about Guadalajara, Mexico, “where Antonio’s grandparents live. His father went to live there, too, many years ago, when Antonio was just a baby.” His world is presented as normative; in fact the illustrations are of a student population at his school, that is predominantly Latino including a Latina teacher, and all except one of the children who are not Latino, are children of color.

Parents and grandparents of the children in this book represent a full range of ages, ethnicities and religious backgrounds. The sentence, “Parents of all shapes and sizes come to greet their children” cues us in to notice the differences amongst these families. We see the racial and gender differences amongst the parents and the children they are greeting easily. On a double take we notice that Leslie, Antonio’s stepmother is taller than the other adults, which seems to be the biggest difference between her and the other adults that Antonio notices, while the other children jeer about her because she “looks like a guy,” and has paint all over her from her work in the art studio, which stimulates them to belittle her as looking “like a box of crayons exploded all over her.” In response, Antonio pulls Leslie away and, despite the fact that he enjoys his time with Leslie after school every day, he asks if he can walk home by himself in the future.

This book feels sad. This is because of the tone set by the illustrations, which convey a persistent sense of yearning and longing in the eyes of almost all the characters. No one ever smiles fully, except in the family drawing Antonio makes of him and his two moms for his mother’s day card. Even when a compromised smile appears on the face of a character, their eyes overshadow any reading of complete fulfillment or happiness with a sense of worry and reflection. Although this sentimentality within the illustrations is a powerful representation of the subtext of Antonio’s worry about ending up lonely if he separates from Leslie in response to his classmates’ teasing, that feeling of a void starts on the first page, despite the fact that the narrative is well paced and complex, without being overwhelming.

While the teasing of the children seems like a mere catalyst for Antonio’s rediscovering and affirming his bond with Leslie, the imagery of the story is as weighty as the emotional milieu created by E.B. Lewis’ illustrations in Jacqueline Woodson’s Each Kindness, a book which was only about the refusal of children to befriend a new student. In Antonio’s Card/La Tarjeta de Antonio, the illustrations allude to what is unspoken in the text—a sentiment of something missing in the lives of these characters who seem to be smiling through emotional pain. Perhaps this is meant to convey the way that Antonio sees his world as one in which no one ever fully smiles and this is the way the illustrator is allowing emotions regarding the absent father who went back to Mexico to influence the text, since the author doesn’t give voice to Antonio’s feelings about his father being gone. What is clear by the end of the story is that one of the things which shames Antonio—Leslie’s splattered paint overalls— becomes evidence of Leslie’s bond with Antonio and his mother—a portrait of his mother that Leslie has painted as a Mother’s Day present. When Antonio sees the painting, his viewing of it becomes the turning point in Antonio’s journey towards family acceptance in face of the adversity of verbal teasing.

There are some who would categorize this story in the anti-bullying category of their collection and while I wouldn’t, the text and illustrations’ depthful representations of a child’s emotional vulnerability to teasing in general and especially in regards to their loved ones, makes this a story that can easily demonstrate how much words hurt in a curriculum on bullying and compassion. But, without a guide, children will easily understand Antonio’s sensitivity toward his stepmom and his peers in this story whose natural complexity and convincing narrative make it well worth its status as a Lambda Literary Finalist. (buy)

Recommendation: Highly recommended; ages 7+

Reviewer: Omilaju Miranda

Marisol McDonald and the Clash Bash/ Marisol McDonald y la fiesta sin igual by/por Monica Brown

Monica Brown once again delivers a captivating protagonist in the character of Marisol McDonald whose bilinguality, red-headed, brown-skinned physical traits, and mixed Peruvian-Scottish-U.S.American ethnic heritage are significant influences on her daily life. Marisol McDonald became one of my favorite children’s literature characters in the first book in this series, Marisol McDonald Doesn’t Match. This time around, Marisol is days away from her eighth birthday. While she doesn’t want to choose clothes or a party theme that match, she does want to see her abuelita (grandmother) for her birthday. However, Marisol must deal with the disappointing reality that, despite the fact that she has been doing chores and saving money for two years to pay for her abuelita to visit, a visa for her grandmother to visit the U.S. takes too much time for abuelita to arrive before Marisol’s birthday. With the strategic use of hand made, individualized party invitations to her diverse, multicultural group of friends, Marisol is able to get her mismatched costume birthday party and her abuelita finds a special, and realistic way to make an appearance. The story is told in a rich, first person point of view, which includes a sprinkling of Spanish in the English version and a sprinkling of English in the Spanish version so the reader always feels as if they are living in Marisol’s authentic bilingual world. Palacios’ painted illustrations add to the overall cheer of enjoying this book. And the dual language, English/Spanish telling of the story allow the reader to read the story in both languages in one sitting or read it in English one day and Spanish the next day.

Monica Brown once again delivers a captivating protagonist in the character of Marisol McDonald whose bilinguality, red-headed, brown-skinned physical traits, and mixed Peruvian-Scottish-U.S.American ethnic heritage are significant influences on her daily life. Marisol McDonald became one of my favorite children’s literature characters in the first book in this series, Marisol McDonald Doesn’t Match. This time around, Marisol is days away from her eighth birthday. While she doesn’t want to choose clothes or a party theme that match, she does want to see her abuelita (grandmother) for her birthday. However, Marisol must deal with the disappointing reality that, despite the fact that she has been doing chores and saving money for two years to pay for her abuelita to visit, a visa for her grandmother to visit the U.S. takes too much time for abuelita to arrive before Marisol’s birthday. With the strategic use of hand made, individualized party invitations to her diverse, multicultural group of friends, Marisol is able to get her mismatched costume birthday party and her abuelita finds a special, and realistic way to make an appearance. The story is told in a rich, first person point of view, which includes a sprinkling of Spanish in the English version and a sprinkling of English in the Spanish version so the reader always feels as if they are living in Marisol’s authentic bilingual world. Palacios’ painted illustrations add to the overall cheer of enjoying this book. And the dual language, English/Spanish telling of the story allow the reader to read the story in both languages in one sitting or read it in English one day and Spanish the next day.

My four-year-old who is rather good at decoding and following a good story didn’t follow all the detailed nuances that go along with Marisol choosing not to match and wasn’t as excited about this story as I was so I put target audience at just slightly older and a better fit for the child who can already read. The quality of the story should make it a favorite for children beyond the age of ten even though they will have already moved on to higher reading levels. For the 5-8 year old reader, new vocabulary is emphasized that will make them excitedly run to the dictionary so they can understand every single word and emotion of this spunky, energetic protagonist. I want to see so much more of Marisol McDonald. Once again, think Madeleine, think Eloise, think Olivia the Pig, think Orphan Annie all updated and in a Peruvian-Scottish U.S.American girl. l I love this character; you and your kids will as well. (buy

Recommendations: Highly Recommended Ages 5-8+

Reviewer: Omilaju Miranda

The Wakame Gatherers by Holly Thompson

Holly Thompson tackles the difficult subject of war with grace and beautiful writing in The Wakame Gatherers. The book begins with a little girl saying, “My name is Nanami—Seven Seas—and I have two grandmothers from two different seas: Gram from Maine, and Baachan, who lives with us here in Japan.”

Holly Thompson tackles the difficult subject of war with grace and beautiful writing in The Wakame Gatherers. The book begins with a little girl saying, “My name is Nanami—Seven Seas—and I have two grandmothers from two different seas: Gram from Maine, and Baachan, who lives with us here in Japan.”

Gram visits Japan, and several pages are dedicated to descriptions and illustrations of the beaches of Maine and Japan, with particular focus on the local color of Nanami’s Japanese hometown. As a translator between her two grandmothers, Nanami helps them compare and contrast their two lands, learns about hooking and preparing seaweed as she takes care to “[use] the right language with the right grandmother.”

Then comes conflict: not in the present, but seeping through from history. The illustrations become dark and ominous as Baachan reminisces about the war. Nanami continues to translate, and understands, “when my grandmothers were my age they were enemies, their countries bombing each other’s people.” The two old women, through their shared granddaughter’s translation, apologize for their countries’ past actions, and in the space of two pages, a feeling of peace and happiness is restored as they return to wakame gathering.

With exquisite illustrations and vivid descriptions, The Wakame Gatherers brings together two cultures by not just acknowledging similarities and differences, but addressing the past. Of additional educational value at the end of the book are a fact sheet about wakame, a glossary of Japanese phrases, and three wakame recipes.

Recommended: Highly recommended. Ages 4-8.

Diversity Children’s Books Website is Live

Mixed Diversity Children’s Book Reviews is officially a website: http://mixeddiversityreads.com/.

The Website, which founder Omilaju Miranda began as a page on facebook is now a full website with blog where you can find books with diverse protagonists by specific category. Books are easily locatable on a drop down menu. The site is dedicated to listing and reviewing children’s and YA books with protagonists who are either: biracial/mixed, transracial adoptee, bilingual, lgbt-parented, single-parented, or gender non-conforming. There is also a magazine where the site will feature writing for, and by children, and an opportunity for parents to send in photos and videos of their children reading or reciting stories and poems. Check out the book site and find the book for your little one today. If you are a writer or interested in communications and publicity, the site is actively seeking children’s book reviewers and interns to publicize and network with schools and libraries.

The Website, which founder Omilaju Miranda began as a page on facebook is now a full website with blog where you can find books with diverse protagonists by specific category. Books are easily locatable on a drop down menu. The site is dedicated to listing and reviewing children’s and YA books with protagonists who are either: biracial/mixed, transracial adoptee, bilingual, lgbt-parented, single-parented, or gender non-conforming. There is also a magazine where the site will feature writing for, and by children, and an opportunity for parents to send in photos and videos of their children reading or reciting stories and poems. Check out the book site and find the book for your little one today. If you are a writer or interested in communications and publicity, the site is actively seeking children’s book reviewers and interns to publicize and network with schools and libraries.

From the Bellybutton of the Moon/ Del Ombligo de la Luna And Other Summer Poems/ y otros poemas de verano by Francisco X. Alarcon

This is a book of free verse poems about the poet’s childhood experiences in nature, travel, and with his family during his visits to his grandparents’ home in Mexico. The poems are filled with simple vignettes of imagery. They are printed first in Spanish then in the English translation. All poems are accompanied by vivid oil painting illustrations. This is a great book to introduce middle school and older elementary children to free verse poetry while imparting the wonder of being a part of the life of grandparents in a different rural country every summer. All children who spend extended vacations with family members during the summer will relate with these poems of familial love and journey and those who visit Mexico will enjoy this celebration of the rural Mexican landscape, lifestyle and Mexican culture.

This is a book of free verse poems about the poet’s childhood experiences in nature, travel, and with his family during his visits to his grandparents’ home in Mexico. The poems are filled with simple vignettes of imagery. They are printed first in Spanish then in the English translation. All poems are accompanied by vivid oil painting illustrations. This is a great book to introduce middle school and older elementary children to free verse poetry while imparting the wonder of being a part of the life of grandparents in a different rural country every summer. All children who spend extended vacations with family members during the summer will relate with these poems of familial love and journey and those who visit Mexico will enjoy this celebration of the rural Mexican landscape, lifestyle and Mexican culture.

Recommendation: Highly Recommended; Ages: 8+

Book Reviewer: Omilaju Miranda

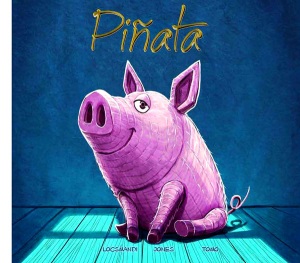

Pinata by Ken Locsmandi and Sebastian A. Jones

Oh, the piñatas talk and I love this book but more importantly, my daughter loves this book. She asked me to read it to her five times the first night and three times the next. It sits atop her dresser like a favorite family photo—her comfort and entertainment. This is the magical Pinnochioesque story of Pancho the Piñata. Pancho is a creation of Jorge the piñata maker who uses a magical, secret, paper mache mix to bring to life piñatas that speak.

Oh, the piñatas talk and I love this book but more importantly, my daughter loves this book. She asked me to read it to her five times the first night and three times the next. It sits atop her dresser like a favorite family photo—her comfort and entertainment. This is the magical Pinnochioesque story of Pancho the Piñata. Pancho is a creation of Jorge the piñata maker who uses a magical, secret, paper mache mix to bring to life piñatas that speak.

Other than the fact that there is only a partial commitment to rhyme in the story, this is a narrative that transports you into a mystical reality and keeps you there. These piñatas enjoy being at the center of a party. Making the children who break them happy is their life mission. With a plentiful smattering of Spanish words of endearment, Pinata tells the story of Pancho maturing from a scared new piñata into a piñata who finds his self-worth in making Lulu, Jorge’s granddaughter happy on her birthday.

Lulu is confined to a wheel chair but that is never mentioned. So, in just a few pages and with the answering of my daughter’s one question about her, “Why does she have that chair?” the story transported differently abled people from unseen in my daughter’s life to normal. Pancho lives on after his candy is spilled and the extra special fantasy of Pinata continues through the other characters, especially the little candy addicted mice that keep the wonder of this world going. Pinata is an exciting, bilingual, magical experience. At the end of the book, you and your child will learn how to make your own, real life, magical pinata. So, turn a page and swing a bat!

Recommendation: Highly Recommended

Reviewer: Omilaju Miranda

Mama, I’ll Give You the World by Roni Schotter

“When Papa was around, Mama loved to dance, but Mama doesn’t dance anymore,” is the first line of Mama I’ll Give You the World and that semi-vague statement is all that is ever said about the absent Papa that lives in the subtext of this children’s story. Perhaps he has passed away, maybe he has abandoned the family; either way, children being raised by single mothers with no father in their lives will feel like their family construct is reflected in Luisa and her mother’s family. Luisa’s mother wants to give Luisa the world that is “so big. So much more for you to know. So much more for you to see.” And that starts every day with Luisa doing her homework beneath a palm tree in the beauty salon and Luisa’s mother saving for Luisa’s college tuition. Doing homework looks exotic, Luisa’s working class world looks like a holiday getaway.

“When Papa was around, Mama loved to dance, but Mama doesn’t dance anymore,” is the first line of Mama I’ll Give You the World and that semi-vague statement is all that is ever said about the absent Papa that lives in the subtext of this children’s story. Perhaps he has passed away, maybe he has abandoned the family; either way, children being raised by single mothers with no father in their lives will feel like their family construct is reflected in Luisa and her mother’s family. Luisa’s mother wants to give Luisa the world that is “so big. So much more for you to know. So much more for you to see.” And that starts every day with Luisa doing her homework beneath a palm tree in the beauty salon and Luisa’s mother saving for Luisa’s college tuition. Doing homework looks exotic, Luisa’s working class world looks like a holiday getaway.

The text is accessible prose that brings the reader smoothly and easily into Luisa’s daily life with her mother in Walter’s World of Beauty– the beauty salon where her mother works. As is so often the case in real life, the salon where Luisa’s mother works is a community gathering place where Luisa’s extended family bonds. The story is a narrative of Luisa communicating with all the adults (hairdressers and clients in her mother’s hair salon) to organize a special gift for her mama—a secret gift that even surprises the reader. Luisa’s dedication to her mother culminates in a climax that made me cry as her daughter celebrates her mother’s birthday by connecting her mother to the past. In the midst of the celebration, the story subtlety introduces a new suitor who has been a trusted friend throughout the book.

Luisa is an observant, sensitive, intelligent character who loves her mom, communicates impressively, and with the realistic precociousness of a child, who while protected by many adults in her life, also lives with the worry about her mother’s happiness and past that overshadows their lives. The illustration is fanciful and engaging, telling the story of the loving community to which Luisa belongs.

Luisa’s world is diverse, filled with people of all races and may ethnicities. Although there are no Spanish words spoken, several of the characters bear Spanish names and the full range of physical features found amongst white, tan and moreno Latinos. Children whose families are from many parts of Latin America—whether the Spanish Caribbean, Central, or South America will feel reflected in the characters represented. Additionally, there are two male hair dressers working with Luisa’s mother—one of whom seems to be slightly effeminate so that without saying it directly, we see that Luisa lives in a diverse and all inclusive world.

Recommendation: Highly Recommended

Reviewer: Omilaju Miranda